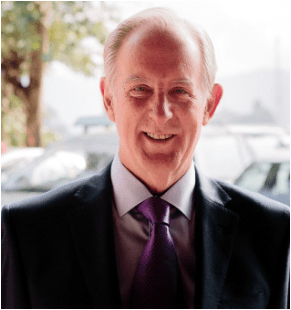

Credit: Francis P. Ankrah Esq., Registrar

A Life Remembered, A Legacy Returned

Howard Roberts turned 80 this September, but the memories that shaped him remain vivid, like the scent of crude oil, which still carries him back to a childhood spent far from the English town of Leamington Spa, where he was born on 4th September 1945. His early years unfolded in Persia and Brunei, where his father worked in the oil fields. Their home in Brunei was made of matted palm leaves, with an oil rig at the bottom of the garden and the sea just down the road. It was a childhood of salt air, distant horizons, and the quiet hum of industry, one that set the tone for a life always looking outward.

Howard didn’t follow the usual path. While his peers settled into careers in England, he trained as a teacher with one goal in mind: to return abroad. When Voluntary Service Overseas offered him a post in Ghana, he hesitated; he had confused it with Guyana. But that mistake turned into a blessing. Ghana, especially Ada Foah, felt strangely familiar. The sea was nearby again. The air was warm. And the people welcomed him with open arms.

One of his first impressions of Ghana came while riding on the back of an open Bedford lorry through the forest near Legon. The sights, sounds, and smells were a world away from the subdued English countryside. But nothing prepared him for the state of Ada Foah when he arrived. The market was several feet underwater for weeks. The river had flooded after all the gates at the Akosombo Dam were suddenly released. It was clear that life in Ada was going to be challenging.

But Howard hadn’t come for comfort. “If I had wanted a less pioneering situation,” he reflects, “then I’d have stayed in England.” Eventually, the market regained its momentum. Kelewele fryers returned, little boys corralled giant edible snails, and palm wine and kachasu sellers reappeared. Market women offered roasted corn with groundnuts, a snack both simple and sustaining.

A Peek into the Good Old Days

From 1968 to 1970, Howard taught mathematics at Ada Teacher Training College. He lodged at the Farmer’s Lodge near Totimekope, sharing the upper floor with Peace Corps volunteers. On the ground floor lived Mr. Desmond Anuforo with his wife, Christy. There was also one Mr. Dosoo, no relation to the College Principal, who lived on campus next door to Mr. Bosomprah and family. Howard remembers the students vividly; their names, their laughter, their small habits. When asked to teach English, he embraced the change. It led to the creation of a college library, built with hand-crafted shelves and mosquito netting, transforming the space into a haven just as African literature was blooming. Students came in droves, drawn by the stories and the quiet refuge the library offered.

His love for storytelling soon found another outlet: drama. He raised a modest stage at the end of the assembly hall, rehearsed with eager students, and once took a play to Big Ada. He watched nervous voices grow strong, shy students step into the light. That transformation, more than any applause, was his reward.

The land itself left a lasting impression. Thunderstorms rolled in like clockwork, pink clouds gathering inland around 4 pm, followed by tropical downpours and winds that bent palm trees. Lizards and crabs scuttled on the ground, owls hissed at night, fireflies danced, and mosquitos (pumi) were everywhere. He caught malaria once, but avoided snakes, except for the time he had to leap over a puff adder sunning itself on a village path..

He still recalls a vivid blue butterfly, larger than his hand, perched on a hospital door of the same colour. At first glance, he thought it had been painted there until it flew away. Occasionally, he borrowed films from the British Council to show to the students. To his surprise, one of their favourites was a cartoon of colourful geometric shapes dancing in sync with music. And on weekends, he was introduced to soul and highlife music at lively dance nights.

He met Ghanaian poet, Kofi Awoonor at Legon, whose haunting line; “The sea eats the land at home” stayed with him. The poem was about Keta, which Howard visited, enjoying the slow ferry ride up the river.

Memories

One exhilarating memory was joining the crew of a local fishing canoe, paddling out to sea in high surf while

a man on shore blew instructions with a whistle. Later, on the beach, he helped haul in the heavy net, chanting “ ahorrg-ba, ahoche ahoche ahoche” with the others. He was gifted a fine fish for supper.

Howard didn’t visit Accra often, but he remembers the bazaar where he bought a much-needed mosquito net, and the Kingsway department store for more suitable clothing. He visited Cape Coast with its tragic history, the opulent presidential palace in Aburi, and the majestic avenue of royal palms nearby. On one trip, he saw the striking Ghana Water Company headquarters high-rise building designed and built entirely by Ghanaians. After Ada, Howard’s journey continued: four years in Zambia, rural development in Malawi, teaching in Jerusalem. But Ghana never left him. His daughter visited the college while studying at Legon. He stayed in touch with Rev. Samuel Boateng. From his home near London, he helped stock a school library in Accra, a quiet echo of the one he built decades earlier.

Now, at 80, Howard holds a gentle wish: to reconnect with his friend, Mr. Anuforo, and to return to Ada Foah one more time. To walk beneath the palms at Otrokpe. To hear the sea. He knows the journey is harder now, but the memories remain luminous.And there’s one more chapter still unfolding. With Francis Prince Ankrah, Esq., the current Registrar of the College, working to revive the Drama Club, Howard has pledged his support. He’s sourced modern English editions and original Shakespearean texts, ready to deliver full scripts. His offer is practical, hands-on where possible, and encouraging where travel is not.

This isn’t just a donation. It’s a homecoming. A way to give back the warmth he received. To help a new generation find their voice, take the stage, and lead. To walk once more if only in spirit, beneath the coconut trees he remembers so fondly.

Howard’s story is a quiet reminder that indeed, a few years of teaching, a few acts of service, can leave a lifetime of belonging.